Hour 1: Israel and Hamas War with Ambassador Rooney

|

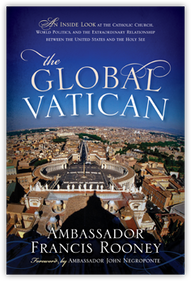

From the centuries-long prejudices against Catholics in America, to the efforts of Fascism, Communism and modern terrorist organizations to “break the cross and spill the wine,” this book brings to life the Catholic Church’s role in world history, particularly in the realm of diplomacy. Former U.S. ambassador to the Holy See Francis Rooney provides a comprehensive guide to the remarkable path the Vatican has navigated to the present day, and a first-person account of what that path looks and feels like from an American diplomat whose experience lent him the ultimate insider’s perspective. Part memoir, part historical lesson, The Global Vatican captures the braided nature of religious and political power and the complexities, battles, and future prospects for the relationship between the Holy See and the United States as both face challenges old and new.

Click to purchase book

THE GLOBAL VATICAN

AN INSIDE LOOK AT THE CATHOLIC CHURCH, WORLD POLITICS,

AND THE EXTRAORDINARY RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND THE HOLY SEE

By Ambassador Francis Rooney

Washington, DC—During a period of immense change and challenge for the United States, the Catholic Church, and the world, Francis Rooney served as U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church, under George W. Bush from 2005 to 2008. His new book captures the interwoven nature of religious and political power and the complexities, battles, and future prospects for the relationship between the Holy See and the United States as both face challenges old and new.

In THE GLOBAL VATICAN (Rowman & Littlefield, November 2013), Ambassador Francis Rooney provides an unprecedented inside look at the Catholic Church, its role in world politics and diplomacy, and the extraordinary relationship between the United States and the Holy See. He argues that U.S. foreign policy has much to gain from its relationship with the Holy See, and vice versa. No institution on earth has both the international stature and the global reach of the Holy See—the “soft power” of moral influence and authority to promote religious freedom, human liberties, and related values that Americans and our allies uphold worldwide.

The timing of Francis Rooney’s assignment to the Holy See came at a momentous period for both America and the Catholic Church. America was four years out from 9/11 and locked in difficult wars in two countries, including a conflict in Iraq—of which the Holy See had strongly and vocally disapproved. The Bush Administration was making progress in bringing democracy, freedom, and stability to Iraq and Afghanistan, but it was difficult on both fronts. And the Catholic Church had its own challenges—the first of these facing Pope Benedict XVI was succeeding the beloved Pope John Paul II. A decline of active participation and growing secularization in much of the Western world threatened the Church at the same time that the abuse scandal continued to expand. Still, the Church remained a powerful moral voice in the world, and Rooney worked with the Holy See to achieve as much diplomatic alignment as possible on crucial issues.

As Francis Rooney argues, the United States and the Holy See remain two of the most significant institutions in world history, one a beacon of democracy and progress, the other a sanctum of faith and allegiance to timeless principles. Despite these differences between the first modern democracy and the longest surviving Western monarchy, Rooney maintains that both were founded on the idea that “human persons” possess inalienable natural rights granted by God. This had been a revolutionary concept when the Catholic Church embraced it 2,000 years ago, and was equally revolutionary when the Declaration of Independence stated it 1,800 years later.

Given our mutual respect for human rights, it seems obvious that America and the Catholic Church would be natural friends and collaborators in world affairs. But this wasn’t the case for nearly 200 years of American history. As THE GLOBAL VATICAN demonstrates, both the United States and the Holy See had to overcome deeply held convictions and perceptions—entrenched anti-Catholicism on the part of Americans; antidemocratic, monarchical reflexes on the part of the Holy See. President Reagan established full diplomatic relations with the Holy See in 1984 because, among other reasons, he realized that he could have no better partner than Pope John Paul II in the fight against communism—and he was right. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Holy See has continued to play a crucial role as a diplomatic force while maintaining formal relations with 179 countries—a number surpassed only by the United States.

The Church is one of the leading advocates and providers for the poor in the world, fights against the scourge of human trafficking, and advances the cause of human dignity and rights more than any other organization in the world. The Holy See also plays a significant role in pursuing diplomatic solutions to international predicaments, whether, for example, promoting peace between Israel and Palestine, helping end the civil war in Lebanon, or helping to secure the release of nearly one hundred political prisoners from Cuba in 2010.

Francis Rooney contends in THE GLOBAL VATICAN that American values and foreign policy goals can be advanced in many parts of the world, including the Middle East, China, Latin America, Cuba, and Africa, through closer diplomatic ties with the Holy See. He notes that the past few years have seen cordial but cooling relations as President Obama has visited the Vatican just once since taking office, and the Obama Administration has demonstrated little more than a perfunctory interest in the Holy See’s diplomatic role in the world. This is a regrettable lost opportunity.

The power and influence of the Holy See is often underestimated. A benevolent monarchy tucked into a corner of a modern democracy, the Holy See is at once a universally recognized sovereign—representing more than a billion people (one seventh of the world’s population)—and the civil government of the smallest nation-state on earth. It has no military and only a negligible economy, but it has greater reach and influence than most nations. It’s not simply the number or variety of people that the Holy See represents that gives it relevance; it’s also the moral influence of the Church, which is still considerable despite secularization and scandals.

As THE GLOBAL VATICAN illustrates, the Holy See advocates powerfully for morality in the lives of both Catholics and non-Catholics, and in both individuals and nations. One may disagree with some of the Church’s positions and yet still recognize the value—the real and practical value—of its insistence that “right” should precede “might” in world affairs. At its core, the Catholic Church is a powerful and unique source of noncoercive “soft power” on the world stage—it moves people to do the right thing by appealing to ideals and shared values, rather than to fear and brute force.

There are limits to the Church’s ability to influence the actions of societies and nations, of course, because it cannot force its will with economic or military leverage. But it is precisely in these failings that its greatness lies—the Church appeals above and beyond might, money, or political power to a deeper recognition in human beings of what is good and right. Ultimately, the Church has power through its consistent defense of enduring principles—it stands for the same thing every day, and in every place.

As the author and historian Hilaire Belloc put it, “the Church is a perpetually defeated thing that always outlives her conquerors.” And Francis Rooney proves that there is much good still to come from the Church, especially in areas where the Holy See and the United States find themselves in alignment.

Hour 2: "Opposition to FCC Regulation of the Internet" with Phil Kerpen, President of American Commitment

|

About our guest: Phil Kerpen

Phil Kerpen, a leading free-market policy analyst and advocate in Washington. He was the principal policy and legislative strategist at Americans for Prosperity for over five years. He previously worked at the Free Enterprise Fund, the Club for Growth, and the Cato Institute. Kerpen is also a nationally syndicated columnist, chairman of the Internet Freedom Coalition, and author of the 2011 book Democracy Denied. Phil Kerpen is the president of American Commitment, dedicated to restoring and protecting the American Commitment to free markets, economic growth, Constitutionally-limited government, property rights, and individual freedom. They engage in critical public policy fights over the size and intrusiveness of government through direct advocacy, strategic policy analysis, and grassroots mobilization. Working with key partners, American Commitment delivers timely, effective public policy research to the broader free-market movement. We are dedicated to restoring and protecting the American Commitment to free markets, economic growth, Constitutionally-limited government, property rights, and individual freedom. https://www.americancommitment.org/ |

https://www.americancommitment.org/fcc-chairs-bad-wi-fi-is-not-a-reason-to-regulate-the-internet/

FCC Chair’s Bad Wi-Fi Is Not a Reason to Regulate the Internet

October 2, 2023

End Regulatory Tyranny

By Phil Kerpen

For two years, starting in 2015, the FCC regulated Internet service providers as public utilities in the name of net neutrality. When the Trump FCC under Chairman Ajit Pai proposed to repeal those Obama-era regulations, the media and other Democrats unleashed a series of apocalyptic predictions.

“End of the Internet as We Know It,” headlined the CNN home page.

“The Internet Is Dying. Repealing Net Neutrality Hastens That Death,” was the New York Times version.

“The repeal of Net Neutrality is an assault on our digital civil rights. This is an issue that will define our times,” was the statement from Senator Ed Markey, typical of Senate Democrats.

Pai followed through on his proposal and made those predictions look ridiculous. The lightly regulated, free-market approach passed the lockdown-era Zoom-boom test with flying colors, with hardly a hiccup as vast amounts of offline activity moved online in stark contrast to regulated Europe.

A CNN headline read: “Netflix and YouTube are slowing down in Europe to keep the Internet from breaking.”

Unfortunately, one of the only places in the United States where the Internet was not working well during lockdowns was at FCC chair Jessica Rosenworcel’s house – and, shockingly, it is possible to rise that position without understanding the difference between your local area network and the Internet.

Last week, Rosenworcel announced a new proposed rule almost identical to the short-lived Obama rule, and her whole speech was framed by the problems with her router:

“We were told to stay home, hunker down, and move life online. So I grabbed what I thought was important at work and moved my office to my dining room table. At home, I kept changing the location of the Wi-Fi router, feverishly trying to identify the sweet spot where the signal would reach everyone in my family. We had two parents, two kids, a too-crowded house, and all of us on the internet, all the time. It was a lot.”

The United States, contrary to liberal predictions of doom, enjoyed a boom in investment, a decline in consumer prices, and rapid increases in Internet speed since Pai repealed the Obama regulations. But Rosenworcel had a janky router, so ignore all that, right?

It would be easy to disregard this latest round of net neutrality as a non-issue, with overheated rhetoric on both sides but no real consequences. That would be a mistake. If we follow the path of heavy-handed regulations we will get less private investment, as we did last time.

The new proposal even explicitly reserves the right to engage in ex-post rate regulation, deciding after the fact that a company charged too much for a service. Who can invest with that threat hanging over their heads?

The FCC argues that it doesn’t matter because of the billions of taxpayer dollars from Biden’s infrastructure bill set to subsidize broadband, but companies will not accept tax dollars to build out networks if they are concerned that regulations will prevent them from reaching break-even on an ongoing basis after the subsidized build-out is complete.

Regulation will therefore result in many places where federal tax dollars flow to government entities to build government-owned networks, despite the fact these have historically been poorly run and racked up huge operating losses.

Worse, there is a real risk of slipping from taxpayer funding and economic regulation to content regulation, with the rationale that public networks must be regulated and managed in the public interest. Some net neutrality advocates have been open about that goal, such as Alex Lockwood, who argued for public-utility regulation of the Internet as a predicate for censoring “climate disinformation.”

The free-market approach that held sway from the commercialization of the Internet in the 1996 Telecom Act to the 2015 imposition of public-utility regulation under the banner of net neutrality was an overwhelming success, and its restoration after two years of the Obama rules resulted in another five years of success.

FCC Chair Rosenworcel should buy herself a good mesh router to deal with her Wi-Fi issues and leave the rest of us alone.

More Debt Without Spending Reform Is Dirty | American Commitment

MORE DEBT WITHOUT SPENDING REFORM IS DIRTY

By Phil Kerpen

Before Republicans agreed to elect Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, a handful of his colleagues demanded the implementation of a fiscal framework to rein in federal spending.

The threat of spending reduction has, however, launched a full debt ceiling “default” panic. The spending interests are trying to cast conservatives as unreasonable and spendthrift Democrats as saviors of our economy for favoring no-strings-attached increases in federal debt.

In the Orwellian world of Washington, the media and other Democrats call what they want a “clean” debt ceiling increase. But what could be dirtier than jacking up the limit on the national credit card with no plan to reform spending?

The rhetorical strategy they deploy to continue reckless spending is to insist the alternative to a naked debt ceiling increase is “default.” But a federal debt default is not a risk as long as there is more money coming into the federal government on a monthly basis than is owed in interest.

Over the past decade, paying interest on the debt consumed about 10 percent of monthly federal revenues, and in no month reached 20 percent. That means a scenario in which Congress does not raise the debt ceiling and the federal government is forced to operate on a cash basis presents no genuine risk of default.

It would be massively disruptive – much of the government would necessarily shut down and bills would not be paid in a timely fashion. But defaulting on the debt would not occur unless Treasury made the irrational decision not to pay bondholders with current revenue.

So-called experts who insist on “correcting” politicians who refer to a debt ceiling lapse as a shutdown are wrong, and Congress could take this deception off the table by passing a law clarifying that Treasury is required to pay bondholders first.

But while the “default” crisis from a lapse in the authority to issue additional debt is fake, the risk of a real debt crisis is visible on the horizon.

The latest long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office show debt reaching a new all-time high of 107 percent of GDP in 2031 and soaring to 185 percent of GDP in 2052. This is driven almost entirely by federal spending, which is expected to remain higher than before the pandemic even after much of the one-time spending ends. Spending then significantly rises starting in 2025 until it reaches 30.2 percent of GDP in 2052.

Revenues for 2022 came in at 19.6 percent of GDP, the second highest level ever recorded – contrary to the predictions of Trump tax cut opponents – and projected revenues are expected to remain well above the historical norm of 17.3 percent of GDP and remain in the 18 to 19 percent range.

Congress must restrain federal spending before we face a real debt crisis in which we actually cannot afford to pay our bills.

Every major spending and debt deal in Congress since 1985's Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act has included negotiations over the debt ceiling. House conservatives were right to demand spending reforms as a condition for raising the debt, and they should hold firm even if it means a government shutdown. The only clean outcome is one that sets spending on a more sustainable path.